It’s been over thirty years since the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in the former Soviet Union republic of Ukraine. It was a scary time, particularly if you were a teenager living abroad in Europe. I was living in Sweden as a Rotary International exchange student in 1986, and in spring that year, experienced my own version of a year of living dangerously as we unexpectedly went through the radiation fallout from the worst nuclear accident in human history. It took me years to collect my thoughts about that time, in a tale of surviving Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

Surviving the Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster

Sweden 1986

The cake smelled delicious. Warm, fresh from the oven, my Swedish host mother had made an effort to bake something special with the first strawberries of late spring 1986. But she was alone in the eating of that sweet dessert. For my host father and myself, it was forbidden fruit in baked form because of what we couldn’t see or smell.

The Swedish government had advised its citizens to avoid the first harvest of the post-Chernobyl spring. Officials weren’t sure about the potential radiation poisoning from soil that had been contaminated by the 1986 nuclear meltdown in the neighbouring Soviet Union. It was recommended to simply not eat anything from the garden for a period of time. My host mother didn’t care about the warnings. She smiled at us as she enjoyed every bite of her cake at the kitchen table.

There was many ‘unknown unknowns’ about the Chernobyl disaster in the early days. Sweden and the rest of Scandinavia experienced the first of two waves of radiation that drifted across Europe over the hours and days following the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Nobody knew anything. The Soviet perestroika of the day didn’t extend to full disclosure about a deadly, catastrophic meltdown impacting hundreds of millions of people. It was only many years later that the world would learn that Chernobyl had been a level 7 nuclear event, the highest classification possible.

There is no taste or smell to radiation. You don’t see it advancing like a dark, ominous cloud, nor can you protect yourself with duck and cover exercises, useless as they are. The fallout may have fallen from the sky with the rain, or drifted through us as we biked to school. The television debates raged about what impact the radiation would have on humans, much less fruits and vegetables. My high-school Swedish was good, but not good enough to keep up with the technical terms being discussed in earnest by international experts. While I couldn’t grasp every word, their serious voices and anxious facial expressions were not comforting. It was a difficult time to be alone in a foreign land.

It must have been even more challenging for my parents. As youth are wont to do, I didn’t worry too much about the impact of my absence from my family back in Canada. As the fallout wafted over my small town in middle Sweden and questions swirled worldwide, my parents must have been beside themselves with worry.

While we spoke a few times over expensive, long-distance lines, I don’t recall pleas to return home before my exchange year was up. My parents likely knew that I would have refused to leave in any case, secure in youthful belief that nothing bad could possibly happen to me. Even a nuclear accident couldn’t put a damper on the best year of my life.

Visiting the Soviet Union

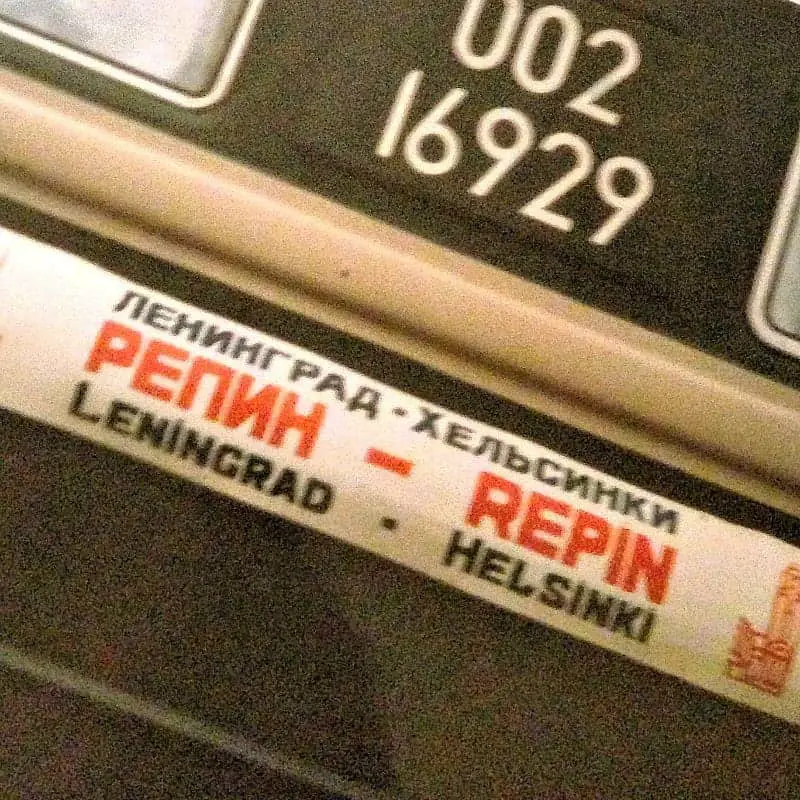

Notwithstanding a nuclear accident, my student exchange year in Sweden was going to be personally memorable for many reasons. I was spending a high school year in a foreign country, without family, friends or familiar sites and comforts. It was an amazing adventure of self-discovery, offering opportunities to make new friends, learn about the world, and visit new places. One of these new places was Leningrad in the Soviet Union, which a group of us visited just one month prior to Chernobyl. The irony of the timing of our visit only struck me years later.

My expat friends and I had leaped at the rare chance to visit the mysterious USSR. Our tour of Leningrad offered a glimpse into the changing perestroika world of Soviet Russia. We could drink Pepsi, and hear the British band The Specials sing their anthem Free Nelson Mandela in our hotel. It seemed familiar, yet it was completely different and alien from any place we’d ever been.

The reality on the ground as we toured Peter the Great’s city on the Neva, remained the celebration of central government control, Stalinist architecture, and reminders of past glory and sacrifice. The glorious Hermitage Museum was populated with glum matrons in grey guarding priceless artworks. The somber Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery to victims of the Siege of Leningrad was as silent as the burial mounds of those citizens who had held out against the Nazis.

There was no inkling of impending nuclear disaster, and little notion on the surface that the USSR was about to undergo its own meltdown and state dissolution a few short years later.

The international and local crises of 1986 – the Challenger explosion, assassination of Swedish Prime Minister Olaf Palme, Chernobyl – were a particular series of unfortunate events that had a profound impact on the world, and on my 17-year old self. They became intertwined with my personal journey of growth and independence.

In surviving Chernobyl and my year away, I experienced a taste of the tragedy and wonder that life has to offer. Like my host mother’s cake, the unknowns may sometimes be the most intriguing part of the experience.

Photo Credit: C Laroye; Max Tikhansky, Shutterstock

- 8 of the most spectacular BC roadtrips - March 28, 2024

- 21 fantastic things to do in Whistler in summer - March 23, 2024

- 7 unique places to experience Ainu culture in Hokkaido - March 22, 2024